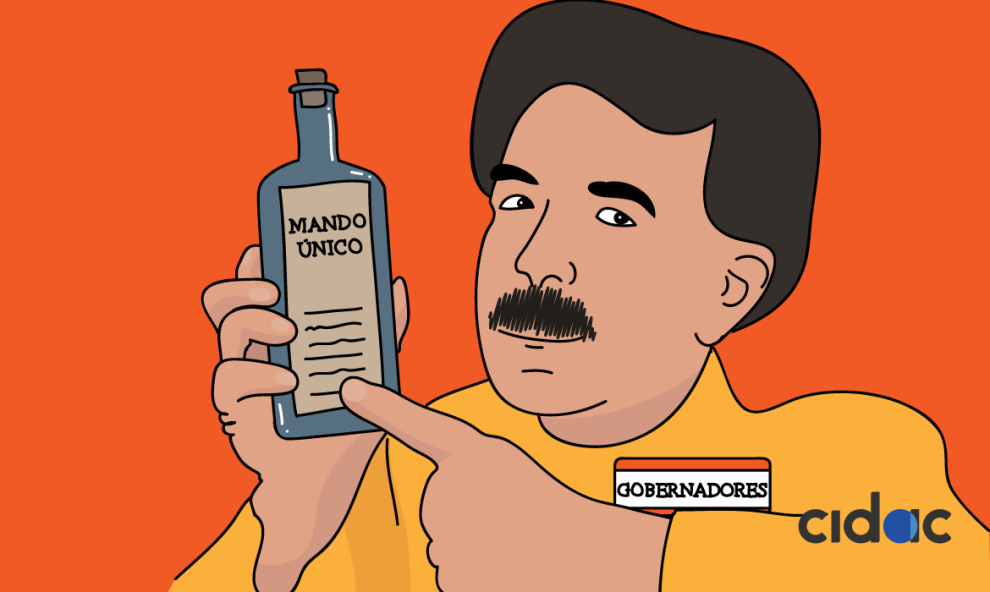

In Greek mythology, Panacea was the goddess of universal remedies: there was no ill she could not cure. That is what the concept of centralized command (mando único) seems like, which in recent years became a mantra: no sooner in position, this one and only police command structure will solve the security problem that the country is undergoing and end of matter.

Let us begin at the beginning: the security problem was not born yesterday and originated in a system of government created nearly one hundred years ago that was never brought up to date. Against what was established as a federal system in the Mexican Constitution of 1917, the political system that in fact emerged with the foundation of the National Revolutionary Party (PRN) in 1929, was a centralized one, pledging to vertical control. The Federal Government made itself responsible for security in view of its decisive weight, utilizing the state governors as mere instruments. Imbued with that same weight it imposed rules on the drug trafficking mafias: more than negotiations, the Federal Government was so powerful that it limited the movement capacity (and damage) of the Narco within the country, with the obvious payment of “donations”. It worked not because Mexico had a modern, professional and functional security structure, but because the Federal Government had the power to control everything.

The country progressed but the system of government continued the same. Progress implied new economic, political and social realities that, de facto, came to limit the capacity of the government, to what we have arrived at today: a dysfunctional government system that does not fit the reality of the country. On the plane of security, the same spirit of control persists but without the instruments to making it effective.

The concept of centralized command at the state level arose from the recognition that the old arrangement had stopped functioning, but it constitutes, in its essence, a reproduction of the old system, albeit at the local level. If conceived as a temporary solution, the centralized command is not a bad solution, but it is far from being perfect because, although it might permit exiting from the immediate crisis, it is not part of a broader plan to transform the system of government. The apparent contradiction is key.

The recent discussion on the centralized command ensued from the assassination of the Municipal President of Temixco and the successive decree to unify the police structure of the state under one command emitted by the Governor of Morelos state. The discussion is peculiar in three respects. First, as soon as “centralized command” is mentioned, an absurd defense surfaces sustained on Article 115 of the Constitution (which establishes the structure of governance of local governments), as if the municipality’s sovereignty were real and, more importantly, as if the great majority of the country’s municipalities were functional in terms of security. Second, the same concept unleashes passions among those who see in the concentration of state power a solution to the problem of security, without realizing the implications of this or the corruption and/or low level of the majority of the state police forces that would be charged with ensuring the security of their states. Finally, the legal weakness of the decree to create the centralized command issued by the Governor is patent, a weakness that, taken to its logical conclusion, would probably be brought down by the Supreme Court if a municipal government chose to challenge it.

Part of the problem lies in that the term ‘centralized command’ is the amalgamation of many other concepts: as if Guadalajara, a big city, were the same as a tiny municipality in the state of Michoacán. There are many municipalities that possess the size and circumstances that should allow them to see to the problem and take responsibility for it, whether they actually do or not. However, there are innumerable municipalities whose economic and institutional frailty implies that they will never have the capacity of constructing a security system of their own. In addition, there are municipalities, such as that of Cuernavaca (capital of Morelos, next door of Temixco), where everything indicates that, instead of advocating the development of a security system, its new government committed itself to “selling the locality” to the highest bidder, inevitably some coterie of organized crime. The Governor’s decree clearly seeks to respond to this fact, but undertakes this within a flimsy institutional and legal framework and, no less importantly, without a vision for the long term.

In that long term, security cannot be imposed. It must be built from the bottom up. Countries that enjoy faultless security have block or neighborhood police officers who know the residents, and who are recognized by the population. As illustrated by the intervention of the Federal Government in Michoacán, the only thing achieved was stabilizing the situation, not resolving it. That stability should have turned into the foundation to construct a new institutional and police framework, but that did not happen. The solution, at least in municipalities (cities) of a certain minimal importance and up, cannot be other than building a new police and security system, under rules that are compatible with the aim of conferring confidence and security on the population. Of course, municipalities lacking the size and capacity to confront the security problem will have to be taken care of under other rules, but the risk that a governor would abuse his or her powers is not small.

The majority of our governors comprise a conglomeration of satraps who perceive their post as a means to get rich or to use that office to run for the presidency. A centralized command police structure conceived as an end in itself would do nothing other than facilitate their capacity to advance in their personal objectives. That is why it is so important to recognize that the centralized command can only serve as a temporary means for building local government capacity. All the rest is no other than a way of preserving a decrepit system of government that is, at the end of the day, responsible for the insecurity that is rife at present.

Comments