“Men will never act well except through necessity: but where choice abounds and where license may be used, everything is quickly filled with confusion and disorder”, affirmed Machiavelli in his Discourses. That is what the debate surrounding the legalization of marijuana seems like. It appears to me that three themes are merged and confused here and that they should be understood, each in its proper dimension.

First is the essential matter of the freedom of each person to do with his life whatever he wants whenever it does not affect third parties. This principle should govern any decision in issues of rules, regulations and control, in whatever ambit, and that of drugs is not distinct. There is no reason to prohibit their consumption in that the sole person affected would be the individual who decides to consume them. The project of Supreme Court Minister Arturo Zaldivar that was approved this week is, in this respect, impeccable.

The second matter is the fact that prohibition has not avoided drugs being grown (or manufactured), transported, or consumed. The sole accomplishment of the prohibition of drugs is the development of enormous consortia devoted to the trafficking of narcotics, the very consortia that, in order to function, generate a mega industry of corruption wherever they are and the violence that inexorably accompanies the latter. On the other hand, one thing is the prohibition of the consumption of determined goods and another, very distinct one, comprises the responsibility of a government to maintain its society at peace. Organized crime proliferates in all societies but not only owing to drugs: also at work are abduction, theft, the black market, gaming, and numberless illicit businesses that must be equally fought against. Deleting drugs from the equation would contribute to diminishing the power of organized crime but would in no way change the responsibility of the State to combat it.

Finally, the third issue is public security, by no manner or means a lesser affair and one that, while obviously linked with prohibition, is not the same as nor does it derive from this. Public security is concerned with the quality and strength of the system of government that a society possesses and that is observed in everything: in the continuity of governmental policies and programs, in the state of education, in the quality of the infrastructure, in the administration of justice and in the respect enjoyed by the police. A strong government (large or not) is one that does not bend with the political winds-at-play but rather functions within a context of laws that effectively limit, through checks and balances, the actions of the politicians who enter and exit the realms of power in consistent fashion.

The nodal point is that decriminalization of the consumption of an innervating substance has nothing to do with public security: this depends on the quality of the government. Although it is obvious that the potential decrease in the earnings of the drug traffickers could contribute to less insecurity, this concerns two distinct issues. In our Mexico’s, in order for drug decriminalization to truly exert an impact on public security it would be the Americans who would have to effect this and not only with Cannabis. The overwhelming majority of narcoprofits derive from the U.S. drug market, thus a significant change in violence in Mexico would not be expected. This is not an argument against decriminalization: only one about the expectation that this would contribute to diminishing the violence.

Spain and the U.S. are two nations in which many more drugs circulate (and are consumed) than in Mexico, but neither of the two is characterized by the levels of violence seen in Mexico on a daily basis. The difference does not lie in drugs being legal or illegal in those nations but instead in that in both there is a solid governmental system that looks after the citizenry. While the conception vis-à-vis drugs is radically distinct in those two countries, the common denominator is the existence of solid judicial power, widely respected professional police forces and effective protections for citizen rights. None of these things is true in Mexico.

Mexico’s decriminalization of the consumption of one of various drugs constitutes a step forward with regard to the principle of individual freedom and that is a milestone in itself. But let’s not ask for the impossible.

Supreme Court

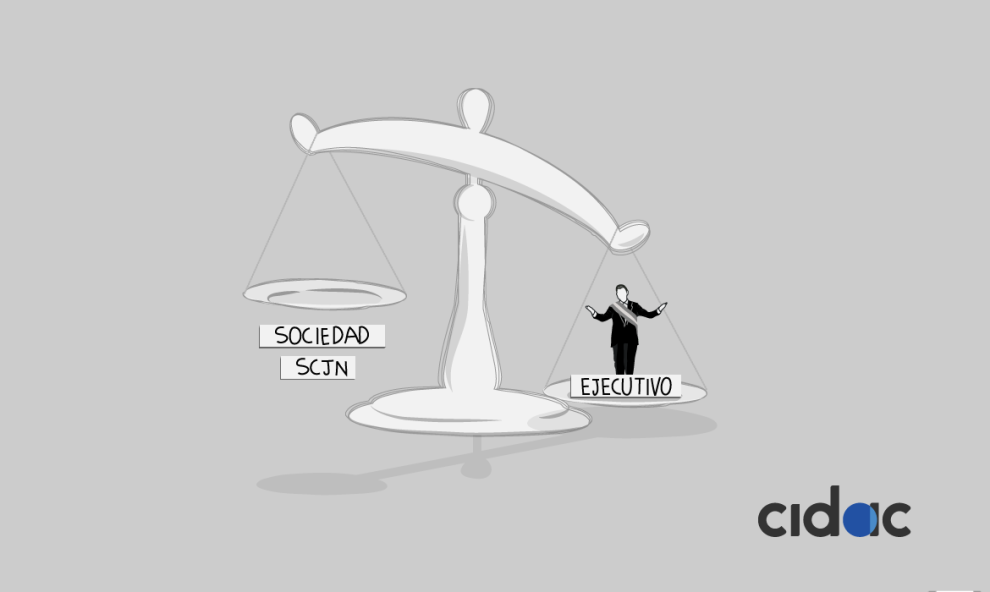

In a system of separation of powers the President proposes and the Congress disposes. That’s the golden rule of checks and balances. However, judging by the controversy regarding the two pending nominations, Mexico continues being a dictatorship. The President is upbraided for not appointing his friends or favorites (as, incidentally, his peers in other latitudes do with frequency). This seems to me an absurd proposal: why would one appoint one’s enemies?

The key is not the president but the Senate, whose function as counterweight consists of evaluating the members of the short list submitted by the president and acting in consequence. In a democracy that is the crucial constitutional control. It is the Senate where all eyes should be focused on to force it to fulfill its crucial mandate and ensure that whoever comes to be a member of the Supreme Court would possess the merit and quality to do so, independently of his friendships. That’s where the society should call to demand democratic accountability.

Harry Truman soon found that “whenever you put a man on the Supreme Court he ceases to be your friend”. That’s the democratic way.

@lrubiof

Comments